On July 30th, the world commemorated World Day Against Trafficking in Persons. It’s a sombre reminder of the invisible chains that still bind millions of people — many of them women and children — to lives of exploitation, abuse, and unimaginable suffering.

Human trafficking is not just a crime; it is a grave violation of human rights that continues to thrive in the shadows of our societies.

Globally, an estimated 50 million people are trapped in modern-day slavery. They are forced to work, sold for sex, or trafficked for their organs — reduced to commodities in one of the most profitable illegal trades in the world.

The International Labour Organization (ILO) reports that two out of every five victims are children, while women and girls make up 70% of those trafficked for sexual exploitation. Behind each number is a name, a family, a future lost.

For many survivors, the trauma does not end once they are rescued. They face the uphill battle of reintegration, stigma, and psychological scars that may last a lifetime. Often abandoned by the very systems meant to protect them, survivors struggle to access justice, healthcare, or therapy — reinforcing a cycle of silence and suffering.

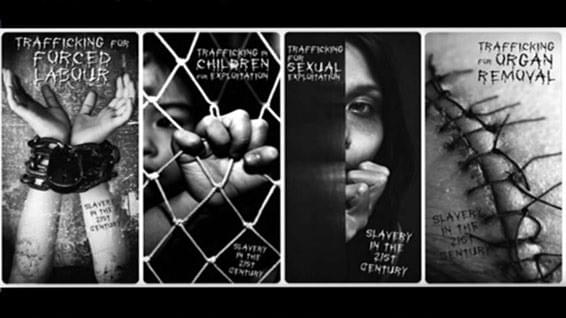

People are trafficked for various reasons — and each purpose represents a disturbing facet of human greed and exploitation. Some are trafficked for forced labour, working under inhumane conditions in farms, factories, domestic settings, or construction sites. Others are trafficked for sexual exploitation, manipulated and coerced into brothels or sold on online platforms.

A third, often underreported, category is organ trafficking — where vulnerable individuals, including children, are abducted or deceived and have organs harvested for black market transplant surgeries. The cruelty of these acts cannot be overstated, and they reflect the depths to which criminal networks will sink in pursuit of profit.

Across Africa, the crisis of human trafficking continues to intensify — driven by poverty, conflict, weak governance, and porous borders. In Libya, harrowing images and testimonies have emerged of African migrants sold in open slave markets.

In the Democratic Republic of Congo, children are trafficked to work in mines under hazardous conditions. And in South Africa, both citizens and undocumented immigrants — particularly women and children — are at constant risk.

In one chilling case in Johannesburg, authorities uncovered 50 Ethiopian nationals, including children, crammed into a truck in Hillbrow in what officials called a clear case of trafficking. The victims were emaciated, dehydrated, and traumatised — many of them having been trafficked through multiple countries.

In other instances, traffickers have used major cities like Sandton as temporary holding points for victims before moving them to brothels or forced labour sites across the country.

One of the most heartbreaking cases in recent memory is that of Joslin Smith, the six-year-old girl from Saldanha Bay who went missing earlier this year. Authorities have not ruled out the possibility of trafficking. Her disappearance sparked a nationwide outcry and drew attention to how vulnerable children — especially from poor or rural communities — are at risk of being kidnapped and sold into trafficking rings that span multiple countries.

In Ethiopia, a historic precedent has just been set. The country sentenced five individuals to death for human trafficking — the first time such a punishment has been issued for this crime. These individuals were convicted for operating along the perilous “eastern route,” a migratory corridor from the Horn of Africa through the Red Sea and Yemen to the Gulf States.

This sentencing came shortly after a maritime tragedy in which dozens of Ethiopian migrants drowned off the Yemeni coast — a horrifying reminder of the deadly stakes in this illicit trade. Ethiopian justice authorities hailed the ruling as a turning point, establishing task forces within law enforcement and judiciary systems to intensify investigations and better protect victims.

While capital punishment is still legal in Ethiopia, it is rarely enforced, making this a symbolic and strategic move in the war against trafficking.

It is not enough to commemorate Human Trafficking Day once a year. Governments must invest in border security, strengthen judicial systems, and provide adequate funding to shelters and survivor-led organisations. C

ivil society must remain vigilant and push for stronger laws and their implementation. Communities must educate themselves and their children about the dangers of trafficking, especially through digital platforms where predators now operate freely.

Human trafficking is not just a foreign problem. It is happening in our neighbourhoods, our schools, our rural villages, our cities. It thrives in silence — and it dies in awareness, resistance, and collective action.

As The Great People of South Africa, we call on every citizen, every policymaker, every stakeholder to take a stand — not only on July 30th but every single day.

Let this be the generation that breaks the chain. Let us not wait until another child like Joslin goes missing before we act.

Human trafficking must end. The time is now.