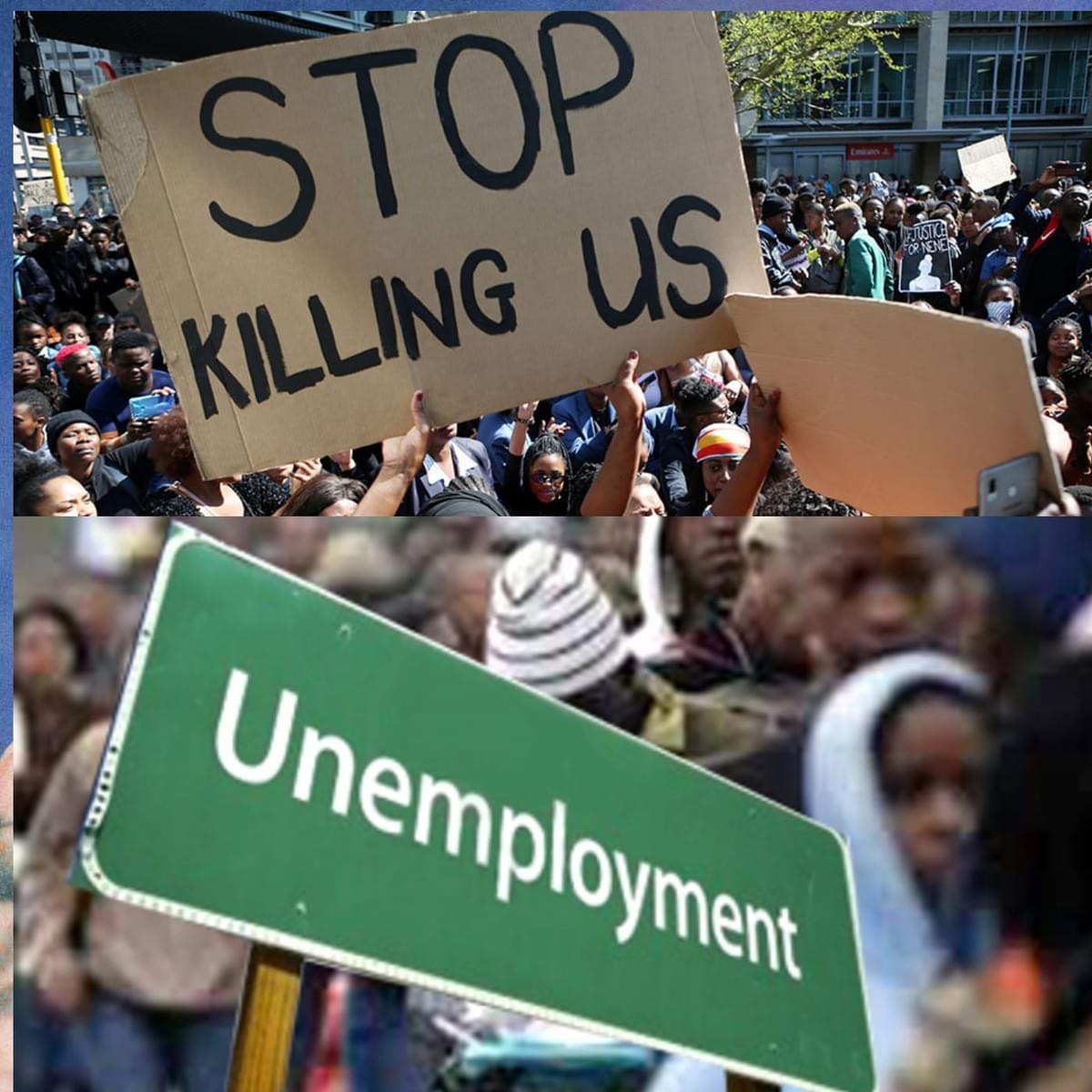

South Africa is in crisis — and women are carrying the heaviest burden. Recent data released by Stats SA has revealed a chilling reality: the women’s unemployment rate has surged to 47%, meaning nearly half of the country’s women who are willing and able to work are unable to find employment.

For Black African women, this number climbs even higher, exposing the layers of racialised and gendered inequality that continue to define our society thirty years into democracy.

But this crisis is not just about the economy — it is about violence, survival, and dignity. When a woman is unemployed, her options diminish. Her ability to leave an abusive relationship fades. Her chances of supporting her children independently are lost.

Her voice is quieted by the weight of poverty. And in that silence, gender-based violence (GBV) festers and flourishes. Women’s unemployment is not a neutral economic indicator. It is a red flag waving violently over a society that continues to deny women safety, opportunity, and power.

Across South Africa, women are trapped in violent relationships not because they want to stay, but because they simply cannot afford to leave. Shelters are overcrowded or underfunded. Legal support is expensive. The job market is unforgiving.

I have met too many women who have whispered to me, with eyes full of pain, “I would have left him a long time ago, but I have nowhere to go.” This is the unspoken reality of GBV — it is not just emotional, physical, or sexual abuse. It is economic imprisonment.

The cost of gender-based violence to the South African economy is staggering. A KPMG study estimates that GBV costs the country between R28.4 billion and R42.4 billion per year.

These figures include direct costs such as medical expenses and legal fees, and indirect costs such as lost productivity, missed workdays, and the emotional toll that is almost impossible to quantify. Violence against women is not only a human rights violation — it is an economic disaster.

And beyond the numbers lies a more heartbreaking truth: the women who could have contributed to our economy are being killed. According to the South African Police Service’s quarterly crime stats, an estimated one woman is murdered every four hours. South Africa has one of the highest femicide rates in the world.

These women are not just victims — they were mothers, entrepreneurs, workers, students, caregivers. They were economic contributors whose lives were cut short by violence. And when they die, the country doesn’t just lose a life — it loses labour, leadership, innovation, and legacy.

The unemployment crisis and the GBV crisis are feeding off each other in a vicious, silent cycle. When a woman cannot work, she is more vulnerable to abuse. And when she is abused, she is more likely to lose her job or become economically dependent. And when she is murdered, her economic potential is buried with her.

This is the cycle South Africa must confront — not with empty promises or policy platitudes, but with bold, systemic intervention.

The soaring unemployment rate among women is not just a failure of policy — it is a betrayal of South Africa’s constitutional promise of equality. And it has real, fatal consequences. It makes women more vulnerable to abuse. It prevents them from accessing justice.

It reinforces generational poverty. And it sends a message to young girls watching from the margins: that your dreams will always be out of reach if you were born female.

Gender-based violence and unemployment are not separate crises. They are deeply intertwined. When a woman has no job, she has no safety. When a survivor cannot feed her children without her abuser’s money, there is no justice. When economic systems refuse to create opportunities for women — particularly Black women, disabled women, LGBTQIA+ individuals, and rural women — then those systems are complicit in the violence they claim to condemn.

If South Africa is serious about ending GBV, it must also be serious about ending the economic exclusion of women. It must invest in job creation that centres women, especially survivors. It must provide free access to trauma counselling, legal support, and skills development.

It must root out workplace discrimination and ensure women are not punished or retraumatized for being victims of violence. We cannot address gender-based violence without addressing poverty and inequality. To be unemployed in South Africa, as a woman, is to live on the edge of danger.

I often say that GBV is not just a war on women’s bodies — it is a war on their futures. And unemployment is the silent battlefield where that war is often won or lost. Every time a woman is turned away from a job interview, every time she is passed over for promotion, every time she is told her trauma makes her “too unstable” to work, the system reinforces her powerlessness.

But I believe that our country is capable of better. I believe that we can build a South Africa where no woman has to choose between violence and hunger. A country where survivors are not just rescued, but restored. A country where dignity is not a luxury, but a right.

We are not asking for favours — we are demanding justice. Because when women work, they heal. When they are employed, they are safer. And when they are economically empowered, the entire nation rises with them.

Let us stop pretending that this is someone else’s problem. Let us stop treating women’s unemployment as an unfortunate statistic. Let us call it what it is: a national emergency.

And let us act like it.