Recently, I had the opportunity to visit the King Shaka Visitor Centre in KwaDukuza, KwaZulu-Natal — a place I had long wished to connect with on a spiritual and cultural level.

I went there not just as a visitor, but as a daughter of the soil, a Black woman who walks with the ancestors and honours the sacred paths laid down by those who came before us. I went to pay my respects to the Lion of the Zulu nation, Shaka kaSenzangakhona, whose vision and power helped shape not only the Zulu Kingdom but the consciousness of a united Black people.

But what I found broke my heart.

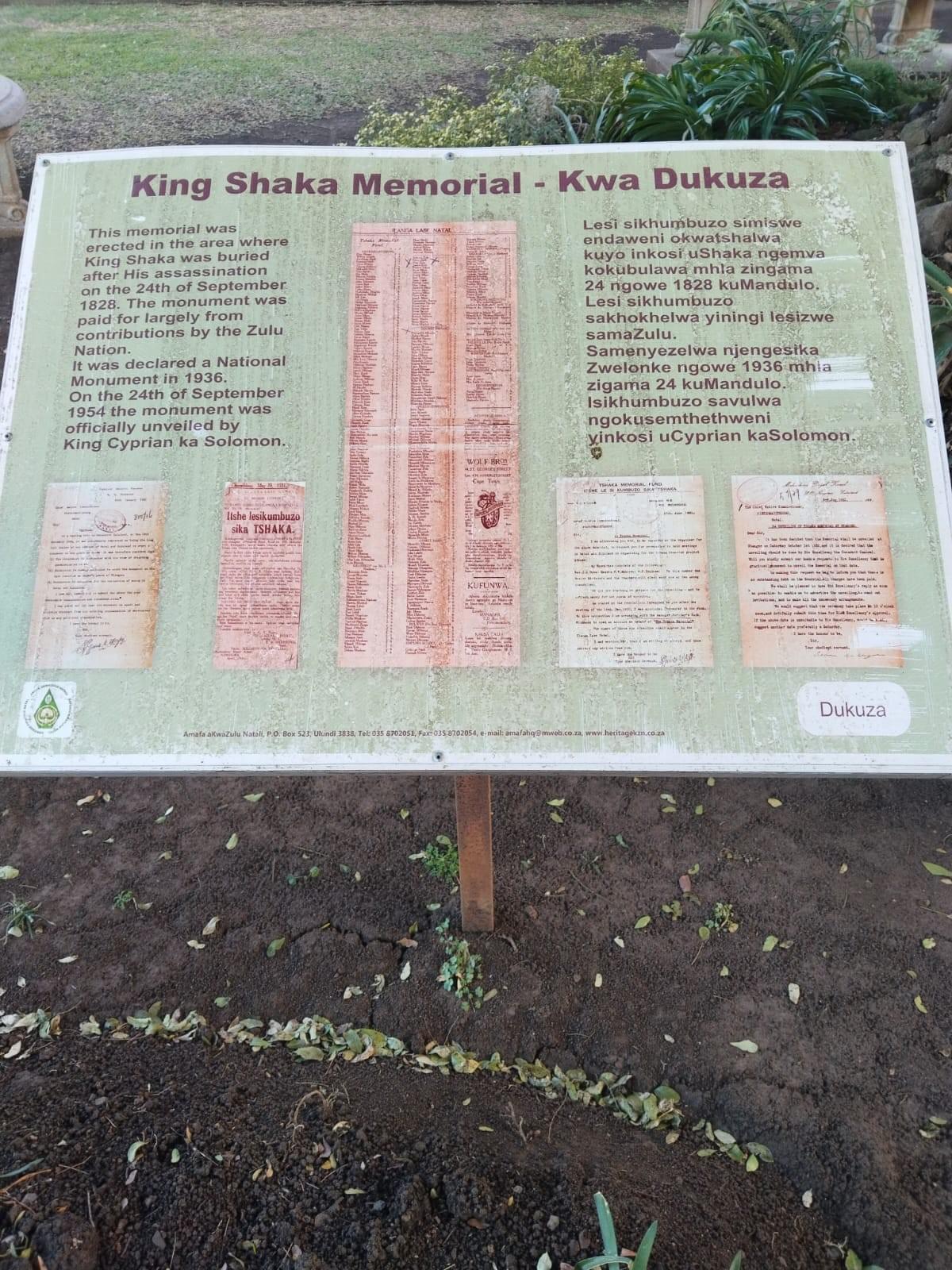

The site is in a shameful state of disrepair. The grounds are overgrown, the buildings neglected, and the energy that should be sacred and serene felt disturbed and forgotten. It is painful to see such a significant piece of our history being left to crumble. This is not what a king’s resting place should look like.

This is not how we honour a man whose leadership echoes through the ages, not just as a military strategist, but as a Pan-African visionary who saw beyond tribal divisions and worked toward unity, pride, and Black liberation.

Growing up in Soweto, I was surrounded by Zulu culture despite being born Xhosa. I went to a Zulu school, sang Zulu songs, prayed in isiZulu, and learned to embrace the beauty of language and cultural exchange.

Today, I speak eight South African languages, and I use them as tools of connection and bridge-building — switching comfortably between isiXhosa and isiZulu, depending on where I am and who I am speaking to. This ability has never made me feel less Xhosa; rather, it has made me more rooted in the idea of collective identity — something that Shaka himself believed in.

That is why the state of this site feels like more than just poor maintenance — it feels like a betrayal of our shared African legacy. Shaka Zulu did not live and lead for us to reduce his memory to weeds and broken bricks. He did not build a kingdom so his grave could be surrounded by noise, neglect, and, sadly, criminal activity.

The area has reportedly become a hotspot for drugs, prostitution, and loud, disrespectful behaviour. There are even buildings around the site that have been unlawfully occupied. This is not only an embarrassment — it is a spiritual violation.

We cry for justice. We cry for land. We cry about losing our history. But here we are, unable to preserve one of the most sacred heritage sites in the country. The silence from those who should be leading this restoration effort is deafening.

Where is our Department of Arts and Culture? Where is the Royal House? Where is King Misuzulu kaZwelithini? Where are the traditional leaders and heritage custodians?

I am calling on His Majesty King Misuzulu, with great respect and urgency, to lead the call for the restoration of the King Shaka Visitor Centre. This site should be a shrine, a place of learning and pride.

A space where people can come to connect with their history, to be inspired by it — not saddened by its current state. It should be a cultural landmark that speaks of strength, unity, and Black excellence.

To my fellow South Africans, especially Black South Africans — this is our duty. The legacy of our ancestors is not something we visit once and forget. It is something we must fight to protect, preserve, and pass down with pride.

King Shaka’s bones may be resting, but his spirit is not at peace. And neither should we be.